THE INTERIOR LAYOUT OF THE RIEZ BUILDING

Photo top left:

Radiator-cover grille in the entrance hall.

Photo top right:

Main entrance of the Riez building.

The sumptuous interior decoration is evidence of Joachim Riez’s status, a merchant who became a company director and finally an industrialist.*

It appears that the decorative scheme was the fruit of a collaboration between the architect Jean-Baptiste Dewin and the De Coene Brothers Art Studio in Courtrai.

Joseph De Coene was a friend of Jean-Baptiste Dewin, who had already commissioned work from his famous firm for previous projects.

The walls of the ground-floor entrance hall are panelled with grey Sainte-Anne marble which is also used to cover the radiators beyond the steps. Warm air from the radiators is diffused via copper grilles decorated with geometric motifs that include small doors decorated with stylised flowers.

Double doors lead to the main hall from where an oak staircase leads to the first floor. The newel posts on the staircase extend vertically into oval shapes that suggest acorns, which are also suggested by the shape of the cupula. The flowing lines may also refer to the design in the stained-glass window described below. The acorn shape can also be seen as the discreet signature of the De Coene firm, which often used it in its work.

The main feature of the stairwell is, of course, the large stained-glass window which originally flooded it with daylight. Following the 1992 extensions, the window no longer admits natural light and is backlit by electric lights.

* These are the successive occupations of Joachim Riez that appear in the Brussels Business and Industry Directories throughout his career. See https://archives.bruxelles.be/almanachs.

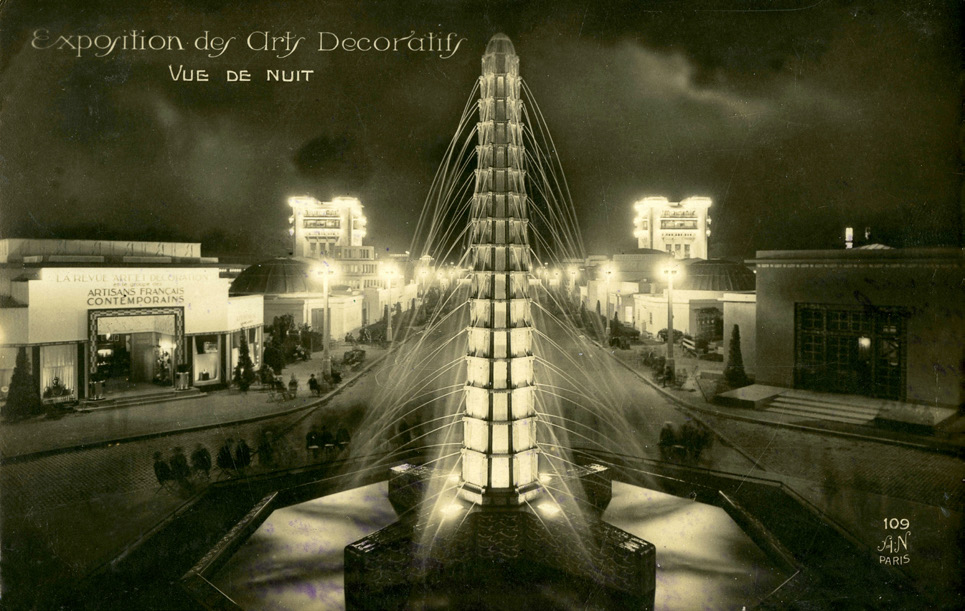

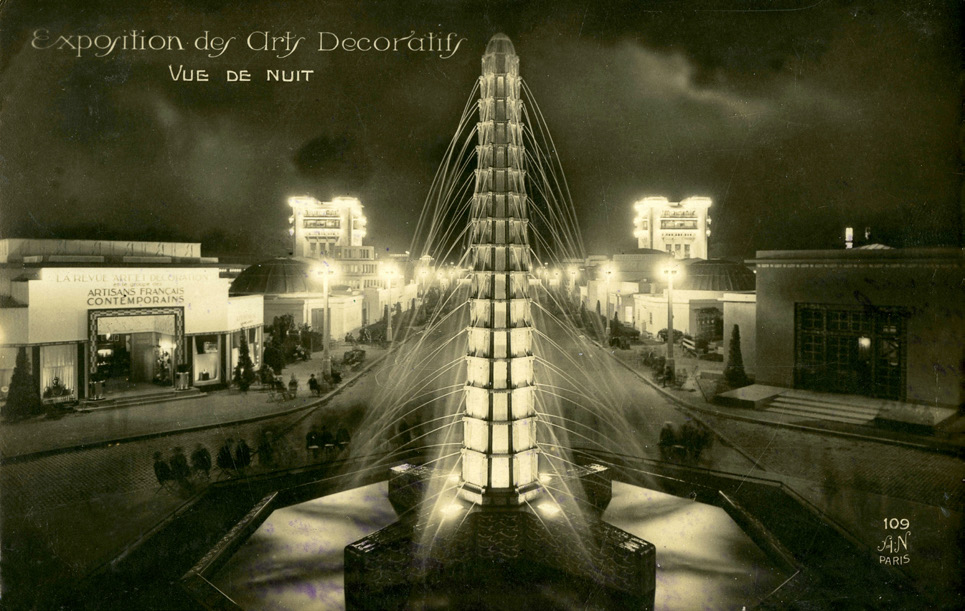

The central motif is a large fountain flowing symmetrically. This type of motif is typical of the Art Deco style, especially following the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts held in Paris in 1925, where visitors were able to admire an impressive 15m-tall illuminated fountain by René Lalique.

René Lalique’s fountain at the Paris Exhibition in 1925. © Art Deco collection of Rheims and the Cities of the Greater East.

On the first floor, the sitting room and dining room are the grandest rooms in the building, where the attention to detail is pushed to its zenith.

As no original plans of the first floor have survived, it is difficult to be sure which of the two reception rooms was the sitting room and which was the dining room. However we can make an educated guess that the first room we come to having climbed the stairs was the dining room, as it is closer to the kitchen. Today it is laid out as a sitting room. Either side of the marble fireplace, with its wood-panelled mantelpiece are two sideboards, whose door keys are signed “De Coene Frères Courtrai”. The bronze key plates of the sideboard doors are decorated with spiral motifs that are typical of the firm’s work.

Sideboard keyplate with spiral motifs and key inscribed “De Coene Frères Courtrai”.

Double doors leading to one of the reception rooms on the first floor decorated with glass bands painted with floral motifs. The door handles on the living room and hall sides are deliberately different in order to blend in with the decor.

Hall and main staircase and a photo of the newel post on the main staircase.

The lower part of the walls are panelled to match the mantelpiece and the sideboards. The walls are divided into sections by bands of carved wood.

The central part of the room has a raised ceiling to show off a magnificent chandelier with a bronze frame, made up of pieces of moulded glass decorated with stylised flowers, also made by the De Coene firm. Either side of this central part, the ceiling is lower, which gives the room a sense of balance and intimacy.

Here, the copper radiator screens are decorated with geometric designs and also with medallions featuring profiles of young women carrying stylised flowers. On this floor, all the window fanlights contain shimmering stained-glass panels depicting baskets of fruit and flowers, which were frequently used motifs following the 1925 Exhibition.

The owners have decided to carefully furnish the rooms in the spirit of the period, including furniture by Jacques Adnet (1900-1984) and Jules Leleu (1883-1961), two French furniture and interior designers who became particularly famous during the Art Deco period.

The light fittings on the landing and some of the office lamps were supplied by the Jean Perzel studio in Paris who, since 1923, have continued the tradition of manufacturing light fittings in streamlined shapes.

Dining-room fireplace flanked by two sideboards.

Overall view of the dining room, used today as a sitting room.

Overall view of the sitting room, today an office.

Structural roof beams on the second floor. Almost an abstract work of art.

The sitting room, today used as an office, is located on the corner and is flooded with beautiful daylight. The radiator screens are topped with yellow Sienna marble shelves and are decorated with stylised flowers in their centres. The matching light fitting is probably also original and made by the De Coene firm.

Since 2003, the walls in both rooms and those of the landing have undergone a restoration by Marianne De Wil, a specialist in decorative paintwork. The current owners have let her take inspiration from the building and the other works of Jean- Baptiste Dewin to create an unusual decorative scheme that brings to mind the Vienna Secession and Art Deco.

An examination of photos taken before the building was restored shows that the walls in the reception rooms were originally decorated with gilded embossed material that looks like leather. This may have been gilded “cardboard stone” a product often used by the De Coene firm, which was one of the first to develop a process of mixing paper pulp with powdered clay and chalk.

A link can be made with the Art Deco sitting room of the De Castillion hotel in Bruges, also decorated by the De Coene firm (1934). Either side of a double mirror are panels of gilded cardboard stone and the light fitting is identical to the one in the Riez building.

Art Deco sitting room of the De Castillion hotel in Bruges. Photo by the author, 2022.

CDA reception in 1982 in the presence of the CDA Chairman, Philippe Clément (making a speech), Irène de Molinari De Frenne, daughter of CDA’s founder (seated on the left), André de Molinari (Managing Director, standing second from left) and Christiane de Molinari-Deschamps (standing on the far right). In the background can be seen the mantlepiece and the walls covered in a gilded material that looks like leather, but which is probably “cardboard stone”.

From the landing, we go through to the kitchen, which can also be accessed from the service staircase. It represents the height of domestic comfort, light and hygiene at the time. Here the wooden parquet floors and panels give way to ceramic tiles that are easier to clean. Shades of grey predominate, with bands of small black-and-white tiles that hint at the Vienna Secession and give the space a sense of rhythm.

At eye level, regularly spaced, low-relief, elongated palmate motifs add a decorative dimension. The same motifs are also reproduced in a large coloured stained-glass window at the back of the room. The original water pump, radiator with integral platewarmer, bell-board to summon the staff and built-in kitchen units have all survived in situ. The second floor of the building is decorated more soberly and is not open to the public. Today it is all used as offices by CDA. The corner room, under the pointed roof, has an open ceiling showing the structural beams.

Stained-glass window at rear of kitchen.

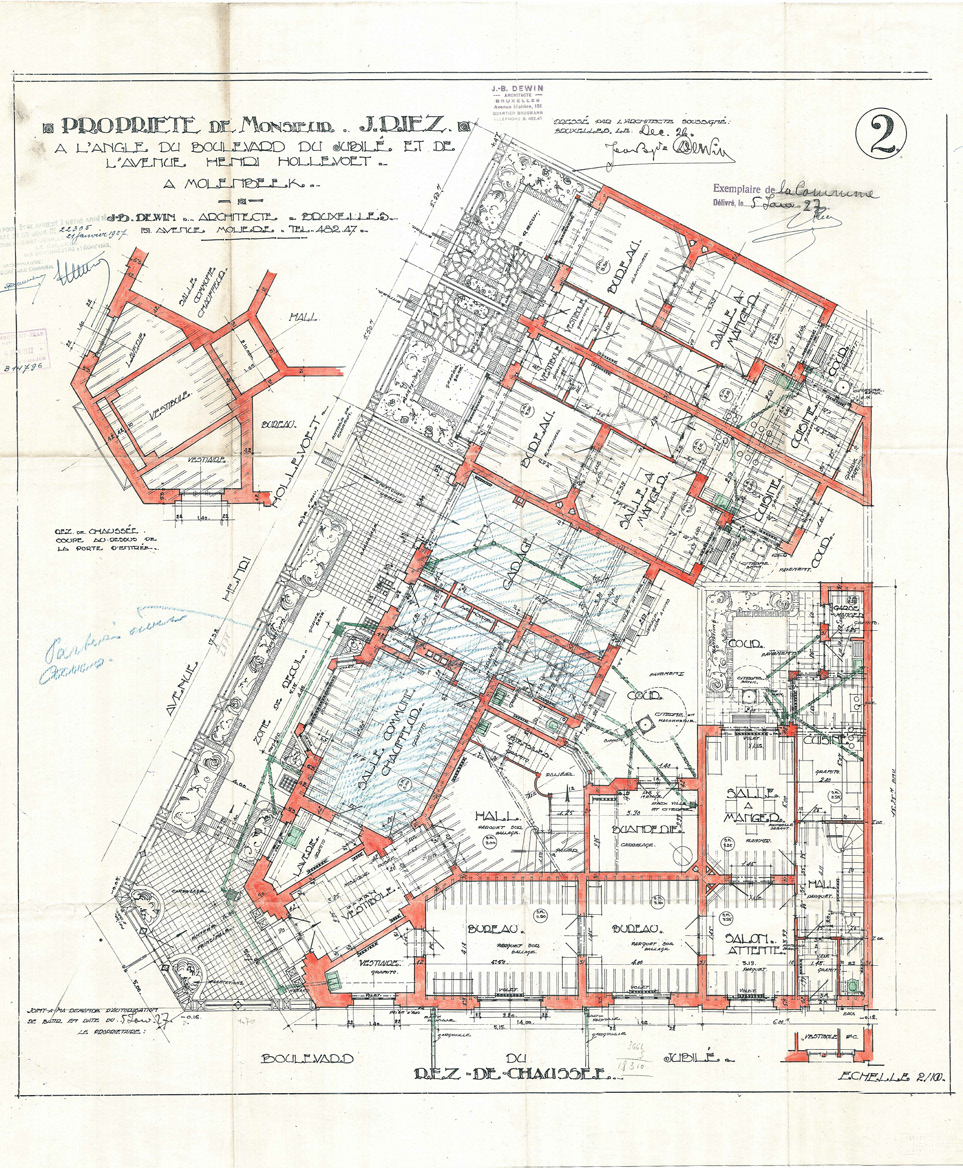

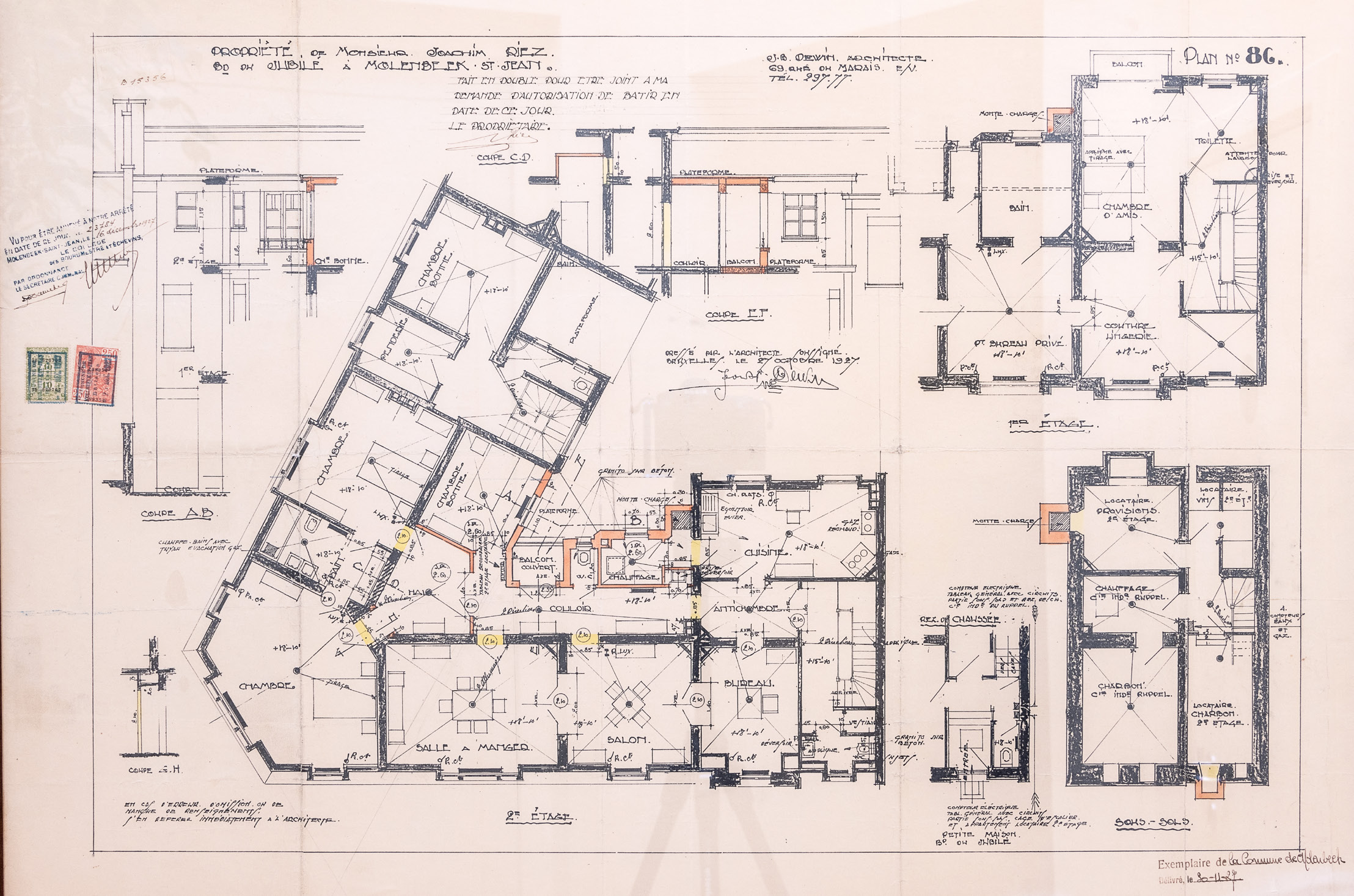

Now let us turn to the interior layout of the residential building. To assist us in this, we have the ground-floor plan submitted as part of the application for the first building permit* (plan 1) and the second-floor plan (including a small part of the first floor and the basement) submitted as part of the application for the second building permit** (plan 2). No complete plan of the first floor exists, but the interior decoration scheme has been so well preserved that it is fairly easy to read how the spaces were intended to be used.

The ground floor (plan 1) is laid out around a central hall (1), from which the main staircase leads up to the first floor. Today, all the rooms are used as offices and extensions have been built into the interior courtyard. Originally, it seems that the space on the Avenue Henri Hollevoet side around the service staircase (2) was used as the garage and accommodation for the chauffeur. On the other side of the building, the rooms that could also be accessed through the front door at 88 Boulevard du Jubilé (3) were the offices used by the Rupel Industrial Company, a dining room and a kitchen.

On the first floor, for which no complete plan has survived, a large central landing leads to a sitting room and a dining room, on the corner and the Boulevard du Jubilé side.

On the Avenue Henri Hollevoet side, accessed by the service staircase (2), is a large kitchen, where the staff probably ate their meals. Finally, on the Boulevard du Jubilé side, are the bedrooms, a bathroom, a study, a sewing room and a guest bedroom (4, plan 2).

The second floor (plan 2), within the mansard attic was given over almost entirely to a self-contained apartment, accessed from the front door at 88 Boulevard du Jubilé (3). However, the space over the ground-floor garage and the first-floor kitchen was separated from this apartment and was an extension of the main apartment on the first floor, accessed via the service staircase (2). It contains a maid’s bedroom, a walk-in wardrobe, probably for the owners’ clothes, and a staff toilet.

Finally, the basement plan (5, plan 2) shows us that the spaces were shared between a coal cellar and storage cellars for the Rupel Industrial Company and the tenant of the second-floor apartment. The Rupel company name on the plan is evidence that Joachim Riez had this prestigious home built for himself when he was preparing to assume his new position as managing director of the renamed company.

* Urban Planning Archive of Molenbeek-Saint-Jean council 14796.

** Urban Planning Archive of Molenbeek-Saint-Jean council 15356.

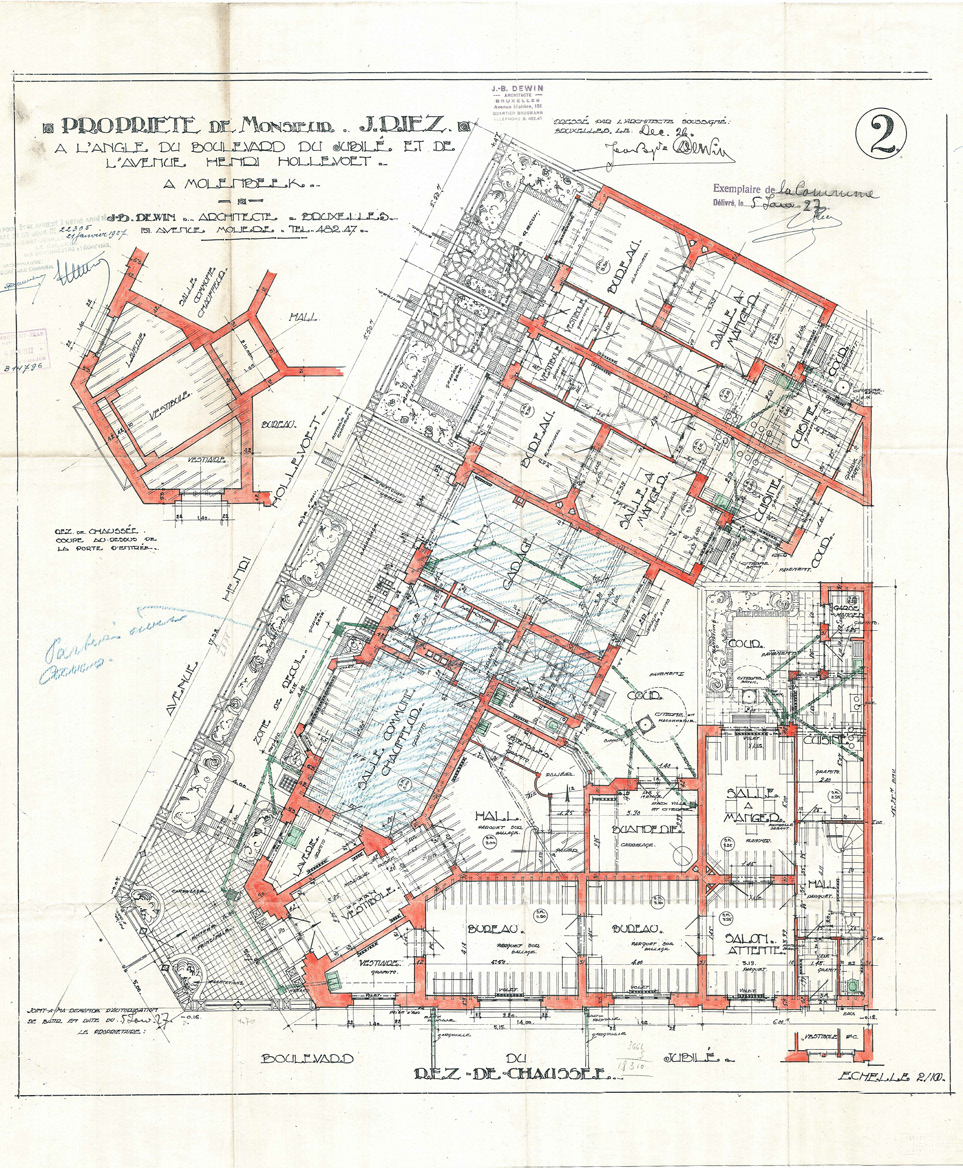

Plan 1.

Ground-floor plan of the building constructed on the corner of Boulevard du Jubilé and Avenue Henri Hollevoet, December 1926. Urban Planning Archive of Molenbeek-Saint-Jean council 14796.

1. Central hall and main staircase.

2. Service entrance and staircase.

3. Entrance to the offices of the Rupel Industrial Company and staircase leading to second-floor apartment.

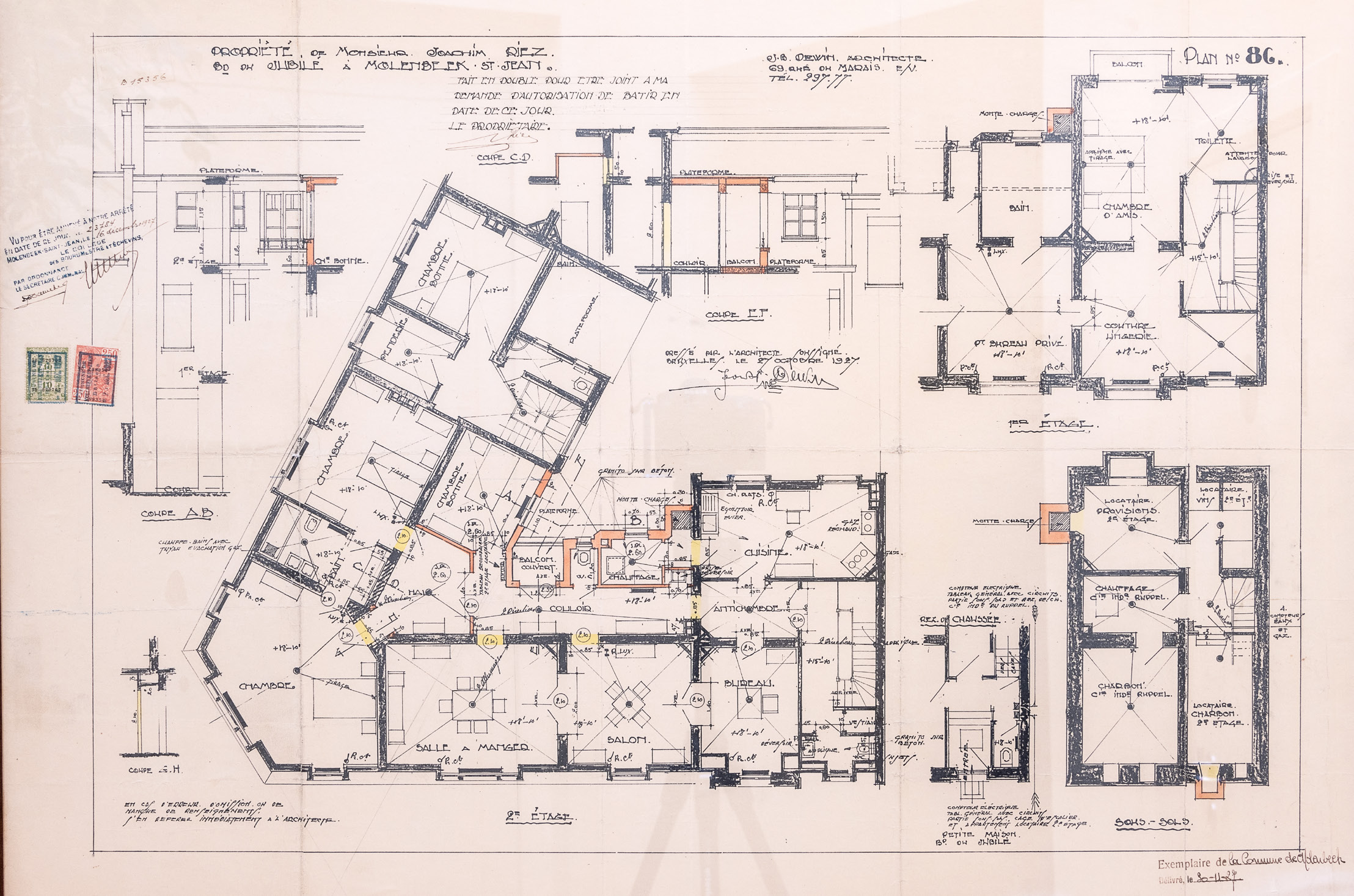

Plan 2.

Plan of the second floor, submitted as part of the application for the second building permit, which made several changes to the first, 1927. Urban Planning Archive of Molenbeek-Saint- Jean council 15356.

2. Service staircase and maid’s bedroom.

3. Staircase leading to second-floor apartment.

4. Sewing room and guest bedroom on the first floor.

5. Plan of basement that mentions the Rupel Industrial Company.

Photo: Main entrance of the Riez building.

The sumptuous interior decoration is evidence of Joachim Riez’s status, a merchant who became a company director and finally an industrialist.*

It appears that the decorative scheme was the fruit of a collaboration between the architect Jean-Baptiste Dewin and the De Coene Brothers Art Studio in Courtrai. Joseph De Coene was a friend of Jean-Baptiste Dewin, who had already commissioned work from his famous firm for previous projects.

The walls of the ground-floor entrance hall are panelled with grey Sainte-Anne marble which is also used to cover the radiators beyond the steps. Warm air from the radiators is diffused via copper grilles decorated with geometric motifs that include small doors decorated with stylised flowers.

Double doors lead to the main hall from where an oak staircase leads to the first floor. The newel posts on the staircase extend vertically into oval shapes that suggest acorns, which are also suggested by the shape of the cupula. The flowing lines may also refer to the design in the stained-glass window described below. The acorn shape can also be seen as the discreet signature of the De Coene firm, which often used it in its work.

* These are the successive occupations of Joachim Riez that appear in the Brussels Business and Industry Directories throughout his career. See https://archives.bruxelles.be/almanachs.

Radiator-cover grille in the entrance hall.

The main feature of the stairwell is, of course, the large stained-glass window which originally flooded it with daylight. Following the 1992 extensions, the window no longer admits natural light and is backlit by electric lights.

The central motif is a large fountain flowing symmetrically. This type of motif is typical of the Art Deco style, especially following the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts held in Paris in 1925, where visitors were able to admire an impressive 15m-tall illuminated fountain by René Lalique.

René Lalique’s fountain at the Paris Exhibition in 1925. © Art Deco collection of Rheims and the Cities of the Greater East.

On the first floor, the sitting room and dining room are the grandest rooms in the building, where the attention to detail is pushed to its zenith.

As no original plans of the first floor have survived, it is difficult to be sure which of the two reception rooms was the sitting room and which was the dining room. However we can make an educated guess that the first room we come to having climbed the stairs was the dining room, as it is closer to the kitchen. Today it is laid out as a sitting room. Either side of the marble fireplace, with its wood-panelled mantelpiece are two sideboards, whose door keys are signed “De Coene Frères Courtrai”. The bronze key plates of the sideboard doors are decorated with spiral motifs that are typical of the firm’s work.

Sideboard keyplate with spiral motifs and key inscribed “De Coene Frères Courtrai”.

Double doors leading to one of the reception rooms on the first floor decorated with glass bands painted with floral motifs. The door handles on the living room and hall sides are deliberately different in order to blend in with the decor.

Hall and main staircase and a photo of the newel post on the main staircase.

The lower part of the walls are panelled to match the mantelpiece and the sideboards. The walls are divided into sections by bands of carved wood.

The central part of the room has a raised ceiling to show off a magnificent chandelier with a bronze frame, made up of pieces of moulded glass decorated with stylised flowers, also made by the De Coene firm. Either side of this central part, the ceiling is lower, which gives the room a sense of balance and intimacy.

Here, the copper radiator screens are decorated with geometric designs and also with medallions featuring profiles of young women carrying stylised flowers. On this floor, all the window fanlights contain shimmering stained-glass panels depicting baskets of fruit and flowers, which were frequently used motifs following the 1925 Exhibition.

The owners have decided to carefully furnish the rooms in the spirit of the period, including furniture by Jacques Adnet (1900-1984) and Jules Leleu (1883-1961), two French furniture and interior designers who became particularly famous during the Art Deco period.

The light fittings on the landing and some of the office lamps were supplied by the Jean Perzel studio in Paris who, since 1923, have continued the tradition of manufacturing light fittings in streamlined shapes.

Dining-room fireplace flanked by two sideboards.

Overall view of the dining room, used today as a sitting room.

Overall view of the sitting room, today an office.

Structural roof beams on the second floor. Almost an abstract work of art.

The sitting room, today used as an office, is located on the corner and is flooded with beautiful daylight. The radiator screens are topped with yellow Sienna marble shelves and are decorated with stylised flowers in their centres. The matching light fitting is probably also original and made by the De Coene firm.

Since 2003, the walls in both rooms and those of the landing have undergone a restoration by Marianne De Wil, a specialist in decorative paintwork. The current owners have let her take inspiration from the building and the other works of Jean- Baptiste Dewin to create an unusual decorative scheme that brings to mind the Vienna Secession and Art Deco.

An examination of photos taken before the building was restored shows that the walls in the reception rooms were originally decorated with gilded embossed material that looks like leather. This may have been gilded “cardboard stone” a product often used by the De Coene firm, which was one of the first to develop a process of mixing paper pulp with powdered clay and chalk.

A link can be made with the Art Deco sitting room of the De Castillion hotel in Bruges, also decorated by the De Coene firm (1934). Either side of a double mirror are panels of gilded cardboard stone and the light fitting is identical to the one in the Riez building.

Art Deco sitting room of the De Castillion hotel in Bruges. Photo by the author, 2022.

CDA reception in 1982 in the presence of the CDA Chairman, Philippe Clément (making a speech), Irène de Molinari De Frenne, daughter of CDA’s founder (seated on the left), André de Molinari (Managing Director, standing second from left) and Christiane de Molinari-Deschamps (standing on the far right). In the background can be seen the mantlepiece and the walls covered in a gilded material that looks like leather, but which is probably “cardboard stone”.

From the landing, we go through to the kitchen, which can also be accessed from the service staircase. It represents the height of domestic comfort, light and hygiene at the time. Here the wooden parquet floors and panels give way to ceramic tiles that are easier to clean. Shades of grey predominate, with bands of small black-and-white tiles that hint at the Vienna Secession and give the space a sense of rhythm.

At eye level, regularly spaced, low-relief, elongated palmate motifs add a decorative dimension. The same motifs are also reproduced in a large coloured stained-glass window at the back of the room. The original water pump, radiator with integral platewarmer, bell-board to summon the staff and built-in kitchen units have all survived in situ. The second floor of the building is decorated more soberly and is not open to the public. Today it is all used as offices by CDA. The corner room, under the pointed roof, has an open ceiling showing the structural beams.

Stained-glass window at rear of kitchen.

Plan 1

Now let us turn to the interior layout of the residential building. To assist us in this, we have the ground-floor plan submitted as part of the application for the first building permit* (plan 1) and the second-floor plan (including a small part of the first floor and the basement) submitted as part of the application for the second building permit** (plan 2). No complete plan of the first floor exists, but the interior decoration scheme has been so well preserved that it is fairly easy to read how the spaces were intended to be used.

The ground floor (plan 1) is laid out around a central hall (1), from which the main staircase leads up to the first floor. Today, all the rooms are used as offices and extensions have been built into the interior courtyard. Originally, it seems that the space on the Avenue Henri Hollevoet side around the service staircase (2) was used as the garage and accommodation for the chauffeur. On the other side of the building, the rooms that could also be accessed through the front door at 88 Boulevard du Jubilé (3) were the offices used by the Rupel Industrial Company, a dining room and a kitchen.

On the first floor, for which no complete plan has survived, a large central landing leads to a sitting room and a dining room, on the corner and the Boulevard du Jubilé side.

Plan 2

On the Avenue Henri Hollevoet side, accessed by the service staircase (2), is a large kitchen, where the staff probably ate their meals. Finally, on the Boulevard du Jubilé side, are the bedrooms, a bathroom, a study, a sewing room and a guest bedroom (4, plan 2).

The second floor (plan 2), within the mansard attic was given over almost entirely to a self-contained apartment, accessed from the front door at 88 Boulevard du Jubilé (3). However, the space over the ground-floor garage and the first-floor kitchen was separated from this apartment and was an extension of the main apartment on the first floor, accessed via the service staircase (2). It contains a maid’s bedroom, a walk-in wardrobe, probably for the owners’ clothes, and a staff toilet.

Finally, the basement plan (5, plan 2) shows us that the spaces were shared between a coal cellar and storage cellars for the Rupel Industrial Company and the tenant of the second-floor apartment. The Rupel company name on the plan is evidence that Joachim Riez had this prestigious home built for himself when he was preparing to assume his new position as managing director of the renamed company.

* Urban Planning Archive of Molenbeek-Saint-Jean council 14796.

** Urban Planning Archive of Molenbeek-Saint-Jean council 15356.

Plan 1.

Ground-floor plan of the building constructed on the corner of Boulevard du Jubilé and Avenue Henri Hollevoet, December 1926. Urban Planning Archive of Molenbeek-Saint-Jean council 14796.

1. Central hall and main staircase.

2. Service entrance and staircase.

3. Entrance to the offices of the Rupel Industrial Company and staircase leading to second-floor apartment.

Plan 2.

Plan of the second floor, submitted as part of the application for the second building permit, which made several changes to the first, 1927. Urban Planning Archive of Molenbeek-Saint- Jean council 15356.

2. Service staircase and maid’s bedroom.

3. Staircase leading to second-floor apartment.

4. Sewing room and guest bedroom on the first floor.

5. Plan of basement that mentions the Rupel Industrial Company.